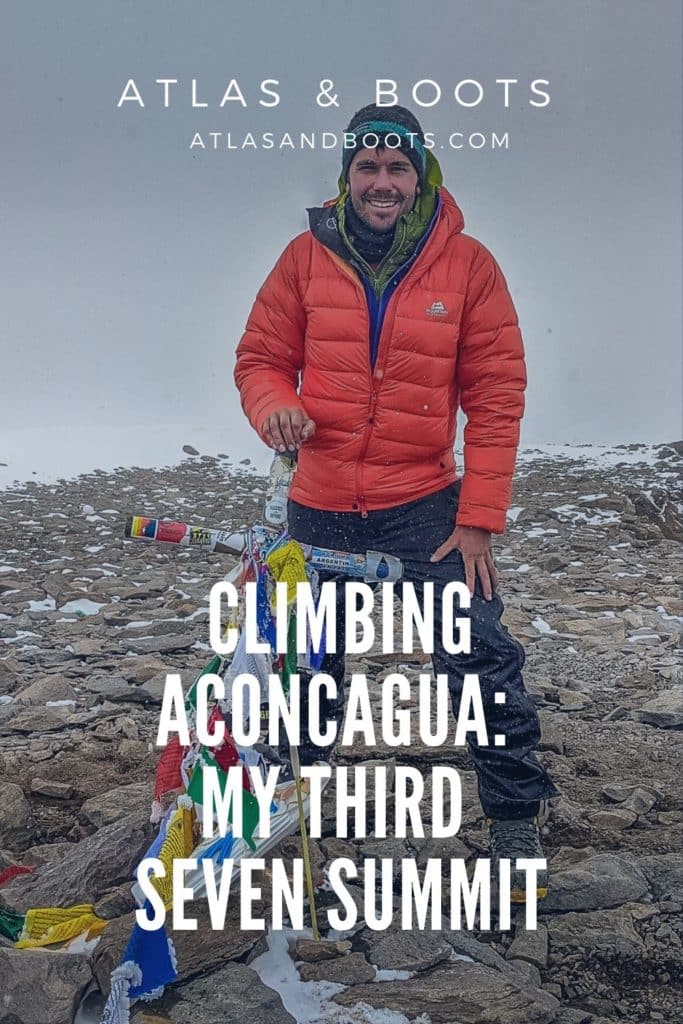

Climbing Aconcagua was the culmination of a 10-year journey and the next step towards realising my ultimate dream: climbing the seven summits

At around 2pm local time on 19th January 2020, I stretched out my hand and tapped the top of the simple aluminium crucifix that marks the summit of Aconcagua at 6,961m (22,837ft).

Looking at the winter climbs taking place at the time in the Himalaya and Karakoram ranges of Asia, and given that our summit time corresponded to around 11pm in Nepal and Pakistan, it is safe to assume that for a few brief moments on that Sunday afternoon, I was the highest person stood on Earth.

Climbing Aconcagua in Argentina was the highest and hardest ascent of my life. It had been on my mountain bucket list for nearly 10 years and took months of planning, preparation and training. Below is my account of my journey to the ‘roof of the Americas’.

Aconcagua gear list

How to climb Aconcagua

Climbing the seven summits: a route to the top

24 interesting facts about Aconcagua

Argentina’s best hiking destinations

Aconcagua: roof of the Americas

Aconcagua is South America’s highest mountain and one of the seven summits: the seven peaks coveted by climbers who want to reach the highest point on every continent. It was my third mountain of the seven after Elbrus in Russia and Kilimanjaro in Tanzania.

I don’t include Kosciuszko in Australia as I subscribe to the ‘Messner List’ which means Kosciuszko is not a seven summit.

| Continent | The "Messner version" | The "Bass version" |

|---|---|---|

| Asia | Everest | Everest |

| South America | Aconcagua | Aconcagua |

| North America | Denali | Denali |

| Africa | Kilimanjaro | Kilimanjaro |

| Europe | Elbrus | Elbrus |

| Antarctica | Vinson | Vinson |

| Oceania | Puncak Jaya (Carstensz Pyramid) | Kosciuszko |

There is no doubt that Kosciuszko is the highest mountain on the Australian mainland. However, the highest mountain on the wider Australian continent (Oceania) – which includes Australia, New Zealand and thousands of islands in the Indian and Pacific oceans – is Puncak Jaya (Carstensz Pyramid) in Indonesia at 4,884m (16,024ft).

Climbing Aconcagua does not require any specialist mountaineering skills. That said, it was a significant step up from any mountain I’d climbed previously. This was largely due to its height and the challenge that comes with climbing at that altitude. Make no mistake: Aconcagua is an exceptionally big mountain.

It may be a non-technical ascent, but at just under 7,000m (22,965ft) it is a long, high and extremely challenging ascent.

Aconcagua is the:

- Highest mountain in the Americas

- Highest mountain the Southern Hemisphere

- Highest mountain the Western Hemisphere

- Highest mountain outside of Asia

- Highest trekking peak in the world

- Second-highest topographically prominent summit in the world

I spent 14 days climbing Aconcagua via the ‘Normal Route’ with Acomara Aconcagua Expeditions. The itinerary is below, although it comes with a certain degree of flexibility depending on conditions on the mountain. There are two additional days built in as reserve days in case of bad weather.

| Day | From/to | Duration | Altitude |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Meet in Mendoza | N/A | 750m |

| 2 | Transfer to Penitentes | 3 hours | 2,725m |

| 3 | Trek to Confluencia Camp | 3 hours | 3,400m |

| 4 | Acclimatisation hike to Plaza Francia | 7-8 hours | 4,000m |

| 5 | Trek to base camp: Plaza de Mulas | 8-9 hours | 4,300m |

| 6 | Rest day at base camp: Plaza de Mulas | N/A | 4,300m |

| 7 | Acclimatisation hike to Mt. Bonete | 7-9 hours | 5,000m |

| 8 | Carry to Camp 1: Canadá, return to base camp | 4-6 hours | 4,900m |

| 9 | Rest day at base camp: Plaza de Mulas | N/A | 4,300m |

| 10 | Climb to Camp 1: Canadá | 3-4 hours | 4,900m |

| 11 | Climb and carry to Camp 2: Nido de Cóndores | 3-4 hours | 5,560m |

| 12 | Rest day at Camp 2: Nido de Cóndores | N/A | 5,560m |

| 13 | Climb and carry to Camp 3: Cólera | 3-4 hours | 6,000m |

| 14 | Summit day and return to Camp 3: Cólera | 12-15 hours | 6,961m |

| 15 | Descend to base camp: Plaza de Mulas | 4-6 hours | 4,300m |

| 16 | Trek out to Laguna de Horcones | 7-9 hours | 2,900m |

| 17-18 | Reserve days for summit | N/A | N/A |

Into the Andes

I met my climbing team in Mendoza, a lively city in the heart of Argentina’s wine country. We were 12 climbers in total, hailing from Argentina, Canada, Norway, India, Israel, Latvia, the UK and Uruguay. We were to begin our climb with two guides, Turco and Nico, who both had years of experience guiding on Aconcagua. Later, at the higher camps, we were to be joined by two more guides.

After introductions, a briefing, kit checks and a last-minute dash to an outdoor store to hire a few bits of kit, the team was ready to leave the comforts of the city and head into the Andes, the world’s longest continental mountain range at 7,000km.

In the morning, we loaded onto a bus and travelled three hours and 170km to Los Penitentes, stopping briefly to obtain our trekking permits at the Ministerio de Turismo in Mendoza.

Los Penitentes was once a popular ski resort, but the last decade has seen the snow practically disappear from its slopes. Today, the rundown collection of chalets and refuges only cater to trekkers and mountaineers in the summer. We settled in a simple refuge for the night and passed the time reading and playing cards.

Our climb began the following morning, although the first day was to be an easy introduction to life on Aconcagua. We transferred 10 minutes down the road to the entrance of Parque Provincial Aconcagua at Horcones, where we began our first day of hiking.

The target for the day was Confluencia Camp at 3,400m (11,154ft) 5km along the trail. The walk was straightforward and undulating, broken up by plenty of photo stops, particularly where the trail passed Laguna de Horcones.

We deliberately took it slow to aid our acclimatisation, stretching the 5km walk to three hours. En route, we caught our first glimpse of Aconcagua, though the weather soon turned and we lost sight of the mountain and got our first taste of snow and the infamous Aconcagua wind.

A sign of things to come

Confluencia, positioned at the confluence of the two rivers flowing from the north and south faces of Aconcagua, is a cosy camp replete with dome tents, bunk beds and real toilets. Pleasantly surprised by how comfortable our lodgings were for the night, we settled in for the first of two nights at Confluencia.

The following morning we took the first of several acclimatisation hikes. We headed northeast along a valley to a plateau known as Plaza Francia below the south face of Aconcagua.

Despite the snow the evening before, I was surprised at how dry and dusty the terrain was. The weather had cleared and the sun was out but the stubborn wind remained. It whipped around my face forcing me to retreat into more and more layers. It would become a recurring feature of the climb: no matter how strong the sun and clear the sky, the wind, and the hostile chill accompanying it, was never far away.

At around 4,000m (13,123ft) we halted our march at a rocky platform to admire Aconcagua rising before us. It was here I realised how colossal Aconcagua actually is. Even at this height, the summit ridge still towers nearly 3,000m (9,842ft) above.

It’s worth noting that in the Southern Hemisphere, unlike in the Northern Hemisphere, it is the south face of mountains which are generally the coldest, iciest and have the most formidable climbing routes. As such, I was relieved to remind myself that we would be climbing Aconcagua via the less hostile north face.

As we turned around and headed back to Confluencia, there was a strange uneasy mood among our group. Our first proper sight of the mountain had buoyed us, but the scale of the task at hand simultaneously became very real and daunting.

Onwards, to base camp

The following morning we bid goodbye to Confluencia and its comforts and began the long footslog to base camp. The eight- to nine-hour trek moves up the Rio Horcones floodplain following the dry, cracked and gravelly riverbed. The wind was a constant source of discomfort throughout, doing its best to whip away any pleasure taken from the unfolding views.

Throughout much of the morning, the 4,952m (16,246ft) Cerro Los Dedos can be seen along the valley ahead. By the afternoon, the trail finally turns to the right and begins to climb steeply towards the source of the river, the Horcones Superior Glacier (not to be confused with the larger but puzzlingly named Horcones Inferior Glacier that descends from the south face of Aconcagua).

After a few false promises, the first multi-coloured specks of Plaza de Mulas base camp finally came into view, much to our relief. It was a weary bunch of souls who stumbled into our camp that afternoon, welcomed by endless thermoses of hot tea and plates of sweet biscuits.

Plaza de Mulas base camp is essentially a more substantial version of Confluencia. While not all climbers and trekkers stop at Confluencia (and if they do, it will be for only two nights at the most) all will stop at Plaza de Mulas and for several nights. We would spend six nights in total at Plaza de Mulas: five during the ascent and one during the descent.

As such, Plaza de Mulas is best described as a sprawling tent town. It houses hundreds of climbers and trekkers, and the guides, cooks and porters who assist them up the mountain.

First summit of 2020

The following day was spent resting before we made our second acclimatisation hike. The nearby Cerro Bonete at just over 5,000m (16,404ft) makes for an ideal target. It takes around four hours to ascend and 2.5 hours to descend.

En route, trekkers pass the now-abandoned Hotel Plaza de Mulas. The building has lain empty since 2009 when the government seized it after the owner stopped paying his taxes.

The higher we hiked the grander the vistas became as views of the Horcones Superior Glacier, the Horcones valley and the north face of Aconcagua – which was looking particularly dark and foreboding in the afternoon light – came into sight.

At this time of year there was little snow around so the climb was another dusty affair. Just below the summit the terrain becomes rocky requiring helmets to be worn and some basic scrambling. It was great to make the summit, also marked by a simple aluminium crucifix, and relax for a few minutes to admire the view. It was my first summit of 2020. But hopefully not my last!

We also got our first views of the wider Andes mountain range. From the summit of Bonete we could see the mountains of the Chilean Andes to the west and Aconcagua to the east. It struck me that Aconcagua, particularly its north face, is not a beautiful mountain by any stretch of the imagination. From this side, there’s little snow to be seen and it’s predominantly surrounded by dry and dusty scree.

There is no pyramidal peak or symmetry to its summit. It is not a graceful mountain, but more a hulking mass of dark rock and moraine. Climbers on Aconcagua, as I am, are here for the glory and bragging rights that come with ticking off the highest mountain on the continent. Good luck to us all, I thought.

The descent back to base camp passed without any real drama. We had to make a detour closer to the glacier as the meltwater had washed away a small bridge, so our group moved some distance upstream to ford the tributaries.

Moving up the mountain

It was time for our first carry to Camp 1, known as Camp Canadá. Plaza de Mulas, as the name suggests, is the last stop for mules, which up until now had carried our heavy duffle bags from Horcones to base camp via Confluencia. We had only been responsible for carrying our daypacks.

However, it was now time to begin moving up to the higher camps and we would be responsible for hauling all personal gear and food from here on. The team did, however, employ porters to aid with carrying the tents and cooking equipment.

The first carry to Camp 1 would double as another acclimatisation hike. We each transferred around 15kg (33lb) of gear to the camp, stashed it beneath tarpaulin loaded down with rocks and then returned to base camp for another day’s rest, before reascending to Camp 1 with another load the day after.

Camp Canadá, positioned behind a rocky outcrop just below 5,000m (16,404ft) enjoys fine views of the surrounding glacier and valley. The trail to Canadá, like all the trails between the higher camps, is a disheartening series of snaking switchbacks taken at a snail’s pace in order to save energy and aid acclimatisation.

After stashing our loads we made short work of the descent, essentially running most of the way down, cutting across the switchbacks that had been so onerous to ascend just hours earlier. Back at base camp we settled back in to enjoy another rest day, before moving up to Camp 1 proper.

Higher camps

Our second carry to Camp 1 was much the same as the first, except on arrival we pitched our tents as we were staying the night this time around. Life at the higher camps is quieter and simpler. There are no dome tents, toilets or support staff, so there are far fewer people. Striking views and crimson sunsets only add to the peacefulness.

However, with the serenity come some hardships. As the altitude increases, the night-time temperature plummets and only a few hardy souls remain outside their tents beyond sundown, unlike at base camp where people mill around post sundown swapping stories.

Likewise, the wind is obviously stronger higher up and further adds to the chill. Sleeping also became harder. I would frequently find myself tossing and turning fitfully, gasping for air that wasn’t there.

Additionally, the toilet situation had changed and become a little more complicated, although arguably more hygienic. More on that in my upcoming article on how to climb Aconcagua!

Two more guides joined our team the following morning to help with the logistics at the higher camps and in preparation for the summit push. We were moving up to Camp 2: Nido de Cóndores (Nest of the Condores) at around 5,560m (18,241ft).

This would prove to be one of the toughest days, as everything we’d carried over two loads from base camp to Camp 1, had to be moved in one carry to Camp 2: around 26kg (57lb).

The necessary switchbacks that come with climbing were utterly punishing with this load on my back. It felt as if it would never end. The only comfort was knowing that there was a final rest day waiting for us the following day and that the loads should be lighter when we moved up to Camp 3.

It is possible to hire porters who will carry up to 20kg (44lb) between the higher camps (see below for details). Many of our team did just this but I, along with three others, stubbornly insisted on carrying our own gear.

Most of us readily collapsed on arrival at Nido de Cóndores (Camp 2), before being roused by our guides: there were tents to be pitched and snow to be melted for water. Nido de Cóndores is a far more substantial campsite than Camp 1, complete with a helicopter landing site and park ranger’s office. Nearly every climber will spend at least one night at Nido de Cóndores.

Many climbers choose to make their summit attempts from here instead of Camp 3 (Cólera). This makes for a much longer summit day and carries a lower success rate, although it does cut down the time spent at the higher altitude and, as such, arguably carries less risk.

We made use of our time at Nido de Cóndores by streamlining our gear, replenishing water supplies and resting as much as possible. We wouldn’t need to carry as much gear to Camp 3, but reports were coming down that there was little snow above so we would need to transport seven litres of water each for cooking our meals and drinking on summit day. Great.

The carry from Camp 2 to Camp 3 turned out to just as gruelling. I carried around 25kg (55lb) and, although the load was slightly lighter, we were now moving up to 6,000m (19,685ft) – higher than I’d ever been before – and the effects of altitude were really beginning to hit home. Breathing was becoming much harder so more rests were needed, making progress even slower.

Camp couldn’t come soon enough and the last thing I needed was a steep scramble over a shelf of rock jutting out below Camp 3. It may have been short, but the final few meters of scrambling took us nearly 30 minutes.

We finally teetered into camp, safe in the knowledge that we still had our tents to pitch, snow to melt, a 3am start and the hardest, coldest and longest day of the expedition ahead of us(!)

Summit day

3am at 6,000m is exactly how you would expect it to be: dark, windy and bitingly cold and altogether a thoroughly hostile environment for a human. I crawled out of my sleeping bag, pulled on practically every layer of clothing I had, wolfed down some toast and tea and braced myself for the day ahead.

The initial climb out of camp under headlamp was steep and we were enveloped in thick fog, but the wind was reasonable and the temperature manageable, which is all one can hope for. After a couple of hours, we reached an old ruined hut known as Independencia at around 6,400m (20,997ft).

It was no longer dark, but that was of little comfort. The fog continued, but by now snow and fierce wind accompanied it. We moved onto the Cresta del Viento traverse, a wild and exposed steady climb around the mountain leading to the Canaleta.

The Canaleta is essentially a slagheap. A soul-destroying slagheap of scree. The mixture of loose gravel and rocks means for every two steps forward you slide back one. It’s 400m (1,312ft) high and takes several hours of slipping, sliding and swearing to ascend.

Finally, we arrived at La Cueva (The Cave), a sheltered cliff face where we paused for hot drinks to fortify ourselves for the final push. By now, we’d lost five members of our team who had been forced to turn back due to exhaustion. The snow was unrelenting, the fog hadn’t cleared, but at least we were somewhat sheltered from the wind.

We continued up the debilitating scree slopes of Canaleta before arriving at the final hurdle: a pile of large boulders just beneath the summit. By now, convinced I was going to succeed, I drew on some final reserves of energy and clambered over the boulders onto the summit plateau.

A clutch of climbers lingered on the summit. The landscape was bleak. On a clear day, I’ve been told the views are stunning, but there was nothing to see. It was a complete white-out, barren and cheerless, but I didn’t care. I wasn’t here to paint a picture.

Instead, I stumbled towards the modest aluminium cross that marks the highest point of the Americas and clumsily tapped my forefinger upon its tip.

On some summits, I have been known to shed the odd tear. On the summit of Elbrus, a month after my mother’s death, I shamelessly wept beneath my goggles. Here, on Aconcagua, I was too exhausted for emotion. Climbing Aconcagua had felt very much like business: the necessary next step of an improbable dream.

The summit day had been too hard to really enjoy or appreciate. The whole morning had been an exercise in endurance and attrition, and it wasn’t over yet. As with any mountain, more accidents happen on the way down so my full attention was still required.

As with most summits, celebrations were short-lived. Thirty minutes later, hugs, fist bumps and summit shots complete, we began our descent back the way we’d come. Four hours later we trundled back into Camp 3, exhausted but relieved.

The gravity of what I had achieved finally began to sink in. I had conquered Aconcagua (as much as anyone ever ‘conquers’ a mountain), the challenge was now largely complete and I could actually enjoy the thrill that comes with topping out on a mighty mountain. Relief slowly turned to elation.

We all plunged into our tents, drank gallons of much-needed tea and did the only thing we could do: sleep.

Descent and hike out

The following morning, we packed up our camp with a spring in our step and descended directly to base camp, stopping at Nido de Cóndores to collect any gear we’d cached during the ascent. Our final night at base camp was our most relaxed and enjoyable as the pressure of climbing was lifted.

Our final day of trekking was the return trip to Horcones, only this time the wind was behind us and we were moving downhill. We stopped at Confluencia for lunch before continuing onto Horcones to meet our transport back to Mendoza and a night in a soft bed.

In a flash, it was all over and time to get back to normal. Aconcagua may not be one of the most beautiful mountains in the world and the ascent is a little short on charm, but this lump of Andean rock and ice will always be one of the most coveted mountains on the planet.

Climbing Aconcagua is a journey to the ‘roof of the Americas’; to the highest peak outside the great ranges of Asia; and for a few moments on a windy day in January, I stood upon its crown and was the highest human on Earth.

Roll on, Denali…

Atlas & BOots

Climbing Aconcagua: the essentials

What: Climbing Aconcagua, the highest mountain in South America and my third seven summit.

Where: The itinerary includes a night before and after the climb at Hotel Raices Aconcagua (or similar) in Mendoza and one night at a refuge in Los Penitentes.

While climbing Aconcagua, most nights are camping in two-man tents. Inka Expediciones provide a lot of the logistical support at Confluencia and Plaza de Mulas, which includes dome tents complete with tables and chairs for mealtimes.

Depending on availability there may be bunk beds available at Confluencia and Plaza de Mulas. The higher camps are much more basic and positioned on rocky ground, so make sure you pack a thick, warm camping mat and ideally a down-filled mattress as well.

Atlas & BOots

Life on the mountain

It should be noted that if the itinerary changes for any reason, then additional accommodation is not provided. We summited a day earlier than planned and financed the extra nights in the hotel in Mendoza at around $65 USD per night.

When: The best time for climbing Aconcagua is from mid-December to the end of January. The climbing season does run from mid-November to the end of March, but the weather is more capricious earlier and later in the season.

Even at the best of times, climbers should be prepared for high winds, snow, ice and temperatures as low as -30°C (-22°F).

How: I joined Acomara Aconcagua Expeditions on a guided climb via the ‘Normal Route’. Acomara have over 15 years of experience guiding and climbing Aconcagua across over 500 expeditions.

Prices start from around $4,000 USD, depending on dates and the itinerary, for a round trip from Mendoza. The price includes all accommodation, meals on the trek, English-speaking guides and assistants, porters to carry equipment between camps and ground transport.

For more information or to book, contact Acomara via email on info@aconcaguaexpeditions.com or info@acomara.com. They can also be contacted via Skype and WhatsApp – check their website for details.

The climbing permit currently costs between $730-$1,140 USD depending on the route and time of year. The current price list can be downloaded from the park’s website. Allow an extra $100 USD per person for tips.

Climbing Aconcagua does not require mountaineering skills, but experience of crampons and high-altitude trekking will be useful. Aconcagua should not be your first high-altitude trek.

Porters can be hired to help with carrying personal gear between the higher camps. These become more expensive the higher you get:

- Base camp to Camp 1: $130 USD

- Camp 1 to Camp 2: $170 USD

- Camp 2 to Camp 3: $260 USD

Phone reception is available at base camp, Los Penitentes and in Mendoza.

I flew to Mendoza in Argentina via Santiago in Chile from the UK with British Airways and LATAM. Book via Skyscanner for the best prices.

I had a long stopover in Santiago so took advantage of the Primeclass Pacifico Andes Lounge inside the international terminal – a godsend after the 14-hour flight from London. The lounge includes a buffet restaurant, hot and cold drinks, shower and washroom facilities and a business area. Prices start at $50 USD for international passengers.

Enjoyed this post? pin it for later…

Cicerone’s Trekking Aconcagua and the Southern Andes is the best guide book available. The book covers two popular trekking routes: the Normal Route and the Polish Glacier Route. However, if you are climbing Aconcagua unguided then the more detailed Aconcagua Climbing Map is essential.