Renowned physician David Sklar tells us about the travel that changed him and why it’s taken him 40 years to write about what happened

David Sklar has faced life-or-death situations hundreds of times in his life and career. As an emergency physician, he has seen humanity at its weakest – and its most triumphant. His experience has led to over 200 published articles, a professorship and an appointment as editor-in-chief of prestigious journal Academic Medicine – a position he held for seven years.

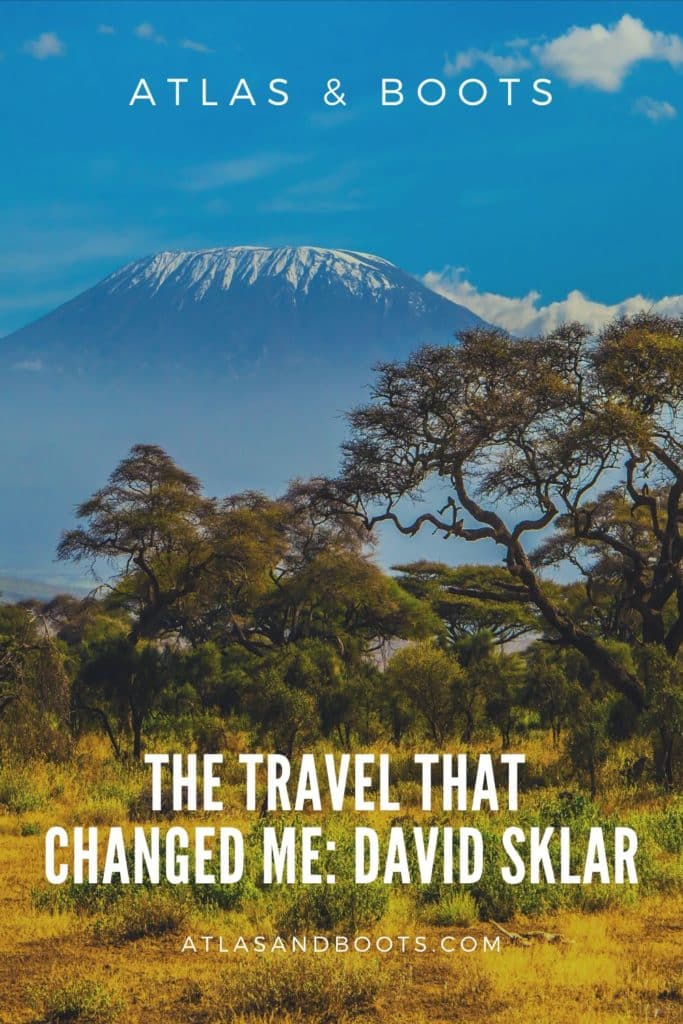

David has saved many lives, but there is one that stands out in his memory. As a young med student in the 70s, David joined a group of tourists on Kilimanjaro, the highest mountain in Africa at 5,895m (19,340ft). During the climb, a fellow trekker fell gravely ill, forcing David to confront what he was willing to do to save the life of a stranger.

Forty years later, David has fictionalised this experience in his upcoming novel, Moonstone Hero. We sat down with David to ask how his experience on Kili changed him and why it’s taken him so long to talk about what happened.

Tell us about the travel that changed you

When I was a medical student in the 1970s, I went to Tanzania as part of my obstetrics and gynaecology training. The women I cared for often lacked prenatal care and experienced serious complications that might have been prevented. I found myself doubting my own fitness as a future doctor, and during a brief vacation from the training I decided to travel up to Mount Kilimanjaro where I hoped I would have an opportunity to climb the mountain and gain some perspective on my medical education, my priorities and the challenges ahead.

The others in my climbing party were from all over the world and each had come to Mount Kilimanjaro for different reasons. They all were young and appeared fit, but as we got higher and higher up toward the peak, most began to experience symptoms of high altitude mountain sickness – nausea, headache, cough – and one of them became so sick that he seemed like he would die if we did not evacuate him.

The situation deteriorated in the middle of the night and I had to face the decision of what I was willing to do, since there were no first aid supplies. I decided we needed to get the young man down to a lower altitude without knowing if he would be able to walk. In the process, I realised that I might die as well as the man we were trying to help. And so I had to face the reality that in my medical career not only would I face the possibility of making errors that could hurt a patient but I could also put my own life at risk. Was I willing to do that?

Did it make you rethink your career in medicine?

I realised that when you make the decision to try to save someone’s life, particularly if you put your own life in danger, you need to understand why you are doing it. Is it your job? Is it the moral thing to do? Is it part of who you are as a person? I felt that the decision was the right one for me and it helped guide me in other dangerous situations.

It has taken you 40 years to tell your story of Kili. Why?

When Covid arrived I had to decide whether I was going to continue to work in the emergency department where we had Covid patients arriving every day. Many friends and family members wanted me to stop because as an older physician, I was at higher risk than my younger colleagues. This was before there was a vaccine and there was not enough protective equipment.

I tried to think back about experiences I had in my life that would help me decide what to do and I remembered the experience I had on the mountain. I felt like it was not fair to expect our residents to put themselves at risk if we attending physicians did not stand with them. I think that this is part of a culture of helping others that we need to encourage in our country and in the world.

after Kilimanjaro, you’ve never had a desire to climb another mountain…

The experience was psychologically and physically traumatic for me. I felt that while I had been lucky to survive, I did not need to push my luck. On the other hand, when I encounter life-or-death situations like responding to Covid in the emergency department or to an earthquake in a developing country, I feel that is part of my responsibility and I’m willing to do that.

Did you stay in touch with the person you saved?

I think it can be very awkward to see someone you have saved. The relationship is unbalanced and I’m not sure the person can ever rebalance it. I’ve visited people I cared for in the emergency department who I know would have died if I had not done something that made a difference. When I’ve visited them later in the hospital they don’t usually remember the details of what happened or who did what. I think that’s probably for the best. We should just take joy in playing what part we can and let the story be our own secret.

Why are some people heroic where others are not?

I like to think that most people in a given situation, like saving a baby that has wandered into the middle of the street, would jump into action. This is where my idea of creating a culture of heroism and courage comes in. I think all of us can be heroes given the right circumstances, but we are often afraid and feel isolated from those around us. And I’m also not sure that we share enough stories of courage around us. I think that if we teach our children why sacrifice for others can be our highest good and share those stories, perhaps we would see more heroism around us.

What has been your number one travel experience?

I have travelled all over the world but number one was when my parents loaded up our car and drove myself and my two brothers and sister from Boston to San Francisco stopping at various national parks like Yellowstone, Yosemite and Grand Tetons, but also cities like Salt Lake City and San Francisco.

I was 15 and my youngest brother was four. My parents were as naive as we were about what the country held in store for us and being able to share those moments of wonder together with them gave me the confidence to continue to explore the world on my own.

Do you count countries?

Yes. I guess it’s part of being a researcher that I tend to do that. We’re always collecting data and trying to reflect what it means. I’ve lived and worked in the Philippines, New Guinea, Tanzania, Nepal, Mexico, Ecuador, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Venezuela, France and Ireland and I’ve visited many others. But to me it’s not about the number of countries we visit, but the people we’ve met and experiences we’ve had in those places.

David Sklar

David on his travels

The best travel experiences I have had as an adult have been when I actually lived in a foreign country for an extended period of time and worked there. I don’t really remember beautiful churches or lakes or waterfalls unless there are people who I can associate with them. Right now I’m living in Ireland as a Fulbright Fellow and what makes it wonderful is the people I have worked with and the problems we’ve solved together. When they take me to their favorite places, that provides a special connection.

Hotel or hostel (or camping)?

When I was younger I loved camping and sleeping out under the stars. Now I prefer hotels. As you get older, different parts of your body tend to break down and you yearn for creature comforts.

Finally, do you still have a dream destination you haven’t seen?

I haven’t been to Cambodia or Laos. Those are places with cultures that have always fascinated me. But I would want to go for a long enough time to get to know the people and places. Maybe a medical mission of some kind.

Enjoyed this post? pin it for later…

An exploration of the uncertain balance between duty and heroism, Moonstone Hero is a thrilling adventure novel, an ode to the medical profession and a timely take on what we owe each other even when it comes at a personal cost.