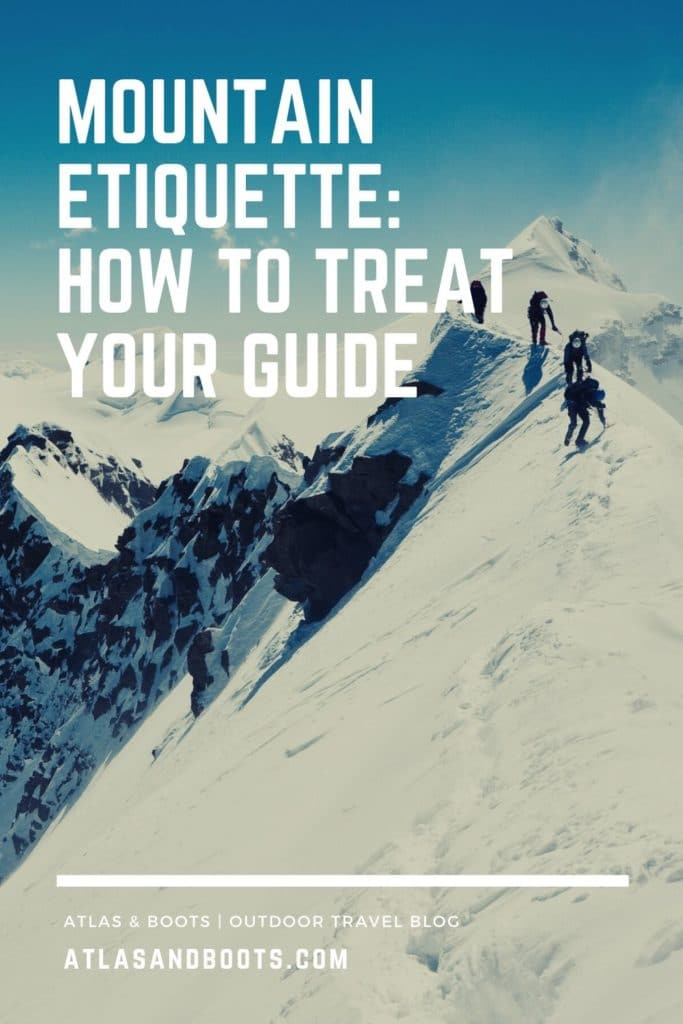

If you’re an adventurer dreaming of great mountains, familiarise yourself with correct mountain etiquette to ensure a pleasant experience for everyone

There’s a moment in Sherpa, the BAFTA-nominated documentary about Everest’s famous guides, where a western tourist asks “can you not talk to their owners?” in reference to the striking Sherpas.

It may have been an innocuous plea made in a moment of frustration but in the harsh truth of film, the question exposes an unsettling attitude to the guides that risk their lives to lead others to the summit.

The question frames the relationship as owner and possession. It reduces the guide to a position of servitude when, in reality, they are in a position of leadership. On the mountain, it is a guide’s responsibility to constantly balance risk with reward, to push as hard as possible without crossing the edge. Theirs is quite possibly the most important job in mountaineering and deserves a commensurate level of respect.

Below, we examine correct mountain etiquette with the help of Guy Cotter, CEO of Adventure Consultants, the pioneers of guiding on Everest and administrators of the Sherpa Future Fund.

Trust your guide

In 2008, climbers Jimmy Chin, Conrad Anker, and Renan Ozturk attempted a First Ascent of Meru Peak’s Shark’s Fin. After 20 days in extreme conditions, they gave up just 100 meters from the summit.

That moment of surrender – that gutting moment of surrender – came about because these world-class climbers were able to recognise the point of no return and make the right decision. Most people don’t have the experience to make a judgement call like this, which is why it’s so important to trust your guide.

Guy tells us: “A professionally trained and qualified mountain guide has been exposed to many different situations in their personal and professional careers, but with the mountain environment being so dynamic there are regularly times when the plan must change because of any one of several factors: weather, conditions, time of day, clients’ fitness or capability and so on. Trust that your guide wants the best outcome for you even though it may not be what you originally signed up for.”

Don’t sweat the small stuff

On our Salkantay Trek to Machu Picchu, we learnt of a client who insisted that a guide and his horse ride from the Peruvian mountains to the nearest village to get more coffee.

There can be no such demands at high altitude. You will be without your creature comforts and some of those you do have, you may lose along the way. Don’t sweat the small stuff. It’s just not worth it.

Naturally, this is a good philosophy for not just mountaineering but all that lies beyond. Guy says: “The mountains teach us what the real priorities in life are and this is helpful when integrating back into our normal world where we can lose perspective on what is really important.”

Be responsible for your own gear

Take responsibility for keeping your gear organised and, by extension, keeping yourself and others safe. A guide can only do so much and it helps if group members actively contribute.

“You don’t need to be exceptional at anything to be a successful high altitude mountaineer, but you can’t afford to be useless at anything either.”

“We are all challenged by different things in the mountains based on our personality type,” says Guy. “Some people find that keeping their equipment together and well organised can be difficult yet they may find they are really good at general mountain movement. For others it is the opposite.

“I have found that climbing very big mountains is like holding a big mirror up to yourself where you see your weaknesses and your strengths in minute detail. By accepting our strengths and working on our areas of weakness we can become rounded mountaineers and achieve great things. I don’t think you need to be exceptional at anything to be a successful high altitude mountaineer, but you can’t afford to be useless at anything either.”

Remember that no-one can control nature

Capricious weather blights even the best-laid plans whether it’s a picnic in a London park or a summit bid on Lhotse.

“Guides want to have good weather and conditions in the mountains as much as you do and an experienced guide will know when the stars don’t align,” says Guy. “We all expect and want things to go according to plan but the reality is that nature is paramount; it doesn’t matter how many people are following your trip and expect you to succeed.”

Facing difficult decisions makes you a better mountaineer, says Guy: “Failure due to correct decision making around the weather and conditions is not actually failure; it is part and parcel of being in the mountains. To be successful in the mountains you need to be really conservative and really pushy at the same time. By that I mean you have to really want it, but you have to be extremely realistic and if all the contributing factors aren’t right you should wait until they are. To use a cliché, you should only strike when the iron is hot.”

Tip well – even if YOU’VE paid a premium price

We’ve spoken before about the awkwardness of tipping and the difficulty of not knowing what is ‘appropriate’. Interestingly, Adventure Consultants have seen everything from a $20 to $15,000 tip on an Everest climb.

Everest veteran Alan Arnette advises: “Five percent of what you paid to the company is a fair tip. It works out best if every member of the team makes the same contribution. Of course if you had an exceptional experience, more may be justified. Five percent for a Rainier trip might be between $50 to $100 where an Everest climb at $50,000 would be $2,500; all reasonable amounts depending on your climb experience.”

Some clients may baulk at the prospect of tipping after paying for a premium expedition, but it’s important to remember that it’s premium for a reason.

Guy explains: “The standard business approach of minimising expenditure to maximise profits is simply not sustainable in mountaineering and certainly not safe for clients or staff. I see many operators in places like Nepal fighting for the bottom of the market and they get a lot of clients who are initially overjoyed by the fact they got a trip for half the price but the reality is you get what you pay for and many of these people go home disappointed or unsuccessful and disillusioned.”

He adds: “I cannot operate in that way and keep a sense of professional integrity. There are people’s lives at stake and it’s a dangerous enough environment already and I cannot understand why people would add a considerable amount of additional risk by going with a flaky operator because it’s cheap. It would be like paying for a major life-threatening surgical operation in a Nepalese back-alley because it’s way cheaper than having it performed by trained surgeons in a real hospital back home.”

Keep the greater good in mind

Guides clearly care for your wellbeing but they are professionally bound to do what’s best for the group. If you want to backtrack 30 minutes because you dropped something, this will seldom be possible.

Guy advises: “If you want to go do a trip that focuses on your objectives and timeframes then you can pay the extra to do a private trip by yourself or with a few close friends. If you are in a group, you have to pitch in both physically and emotionally to support the team.”

Learn some of the local language

There’s very little that delights a local as much as hearing their language on the tongue of a tourist. It shows that you have taken an interest in their culture and not just ticking a box on your mountaineering calendar.

“At least learn the names of those around you who are helping you on your journey,” says Guy. “It’s disappointing to see people point at a staff member they have been on a trip with for a week and say ‘that one there’ rather than their name.”

Leave no trace

Guides and porters will do as much as possible to minimise the group’s footprint, but their time and resources are limited especially at altitude. As such, please take an active role in ensuring the environment is left as clean and undisturbed as possible.

“We have to realise we always leave some trace no matter how diligent we are so we must be especially vigilant with ensuring we minimise our footprint,” says Guy.

Nature is at its most glorious in the mountains. With consideration and effort from all of us, we can help it stay that way.

Enjoyed this post? pin it for later…

Adventure Consultants offer 72 expeditions, treks, backcountry skiing adventures and wilderness journeys to the Himalaya, Antarctica, South America, Greenland, Alaska and the Seven Summits, in addition to a world class guiding service and climbing schools in New Zealand and Europe.