A new study suggests that using trekking poles may not conserve energy, but does “save the legs”. We dig deeper into the science

On a recent trek through the Fann Mountains of Tajikistan, one of our group completed the nine-day foot journey without poles. At some point during the trek, every one of us asked him why he didn’t have them (I’m sure he grew tired of fielding the question) and took turns to recount their many benefits.

We told him that using trekking poles improved balance, reduced load on joints and muscles, aided with walking downhill and carrying heavy packs, made you hike faster and even helped you burn more calories (not really a good thing on a long trek). None of us though, knew any real science to back up this received wisdom.

Unsurprisingly, trekking pole manufacturers frequently claim that it’s been “scientifically proven” that using poles can reduce lower limb joint forces by as much as 25%, often citing a 1999 study in the Journal of Sports Science.

Fortunately, there have been a number of new studies drawing on the latest available technology.

A geographical divide?

One thing to come out of our discussion was that using trekking poles seems to be more commonplace in Europe than in North America and other parts of the world. I was one of only two Europeans while the rest of the group was made up of Americans, Indians, an Australian and a New Zealander.

“You just don’t tend to see them that much in Australia,” the Sydneysider who was sans-poles told us.

“It’s the same in New Zealand. People will look at you funny if you use them on the trails back home,” the Kiwi chimed in. The others all agreed that trekking poles are less prevalent outside of Europe. A quick internet search suggests their claim is more than just anecdotal.

Trailrunner, journalist and pole convert Adam Chase wrote in a 2022 article for Outside Magazine that he believes “one reason American trail and ultrarunners consistently lose races to their European counterparts is that their continental competition consistently trains and races with the aid of poles on their long, steep trails.” Let’s see if the science supports his theory.

What does the science say about using trekking poles?

In 2020, a review by Ashley Hawke and Randall Jensen published in Wilderness and Environmental Medicine journal summarised the various pros and cons of using trekking poles. The review largely confirmed most of the aforementioned arguments: that hikers tend to walk faster and take longer strides with poles, particularly while carrying a pack or climbing a hill; that balance and stability were increased; and that load on joints was reduced, especially when walking downhill.

However, the review also noted that the “negative effects of using trekking poles include increased oxygen uptake (VO2) and energy expenditure (EE), as well as increased loading of the upper extremities”. All of this would lead to burning more calories while also increasing the likeliness of fatigue which basically combats the benefits of using trekking poles.

The latest analysis is the most technical to date and comes from Nicola Giovanelli who is an Italian mountain runner, coach and sports science professor at the University of Udine. His study, published with five colleagues in the European Journal of Applied Physiology, focuses on whether poles “save the legs” when climbing uphill.

Their experiments used an adapted treadmill with an extra-wide belt so that subjects could use trekking poles on it. It could also replicate inclines of up to 45° – which due to a quirkiness in mathematics is classed as a 100% grade or slope – equalling the steepest treadmill in the world built by the University of Colorado Boulder in 2015.

The trials put 15 male trail runners through a series of tests with and without trekking poles, first on the adapted treadmill and then up real mountain terrain outdoors. On all occasions, the incline was sufficiently steep to ensure the participants walked rather than ran up the slope.

The subjects wore portable VO2 analysers to measure their aerobic exertion and insoles in their shoes to measure the force exerted by their feet into the ground (foot force aka Fforce). The poles were equipped with force transducers below the handgrips to capture how hard they were pressing into the ground with their poles (poling force aka Fpole). The test also recorded the subjects’ ratings of perceived exertion.

Key findings

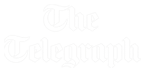

One significant finding was that as the incline got steeper, the participants became more reliant on their poles. The below graph demonstrates their poling force (on the vertical axis) as a function of incline in degrees (on the horizontal axis) during the incremental treadmill test.

More significantly though, the study found that using trekking poles dulls the increase in leg force on steeper slopes and that the subjects who used the most polling force had the most significant force reduction in their legs.

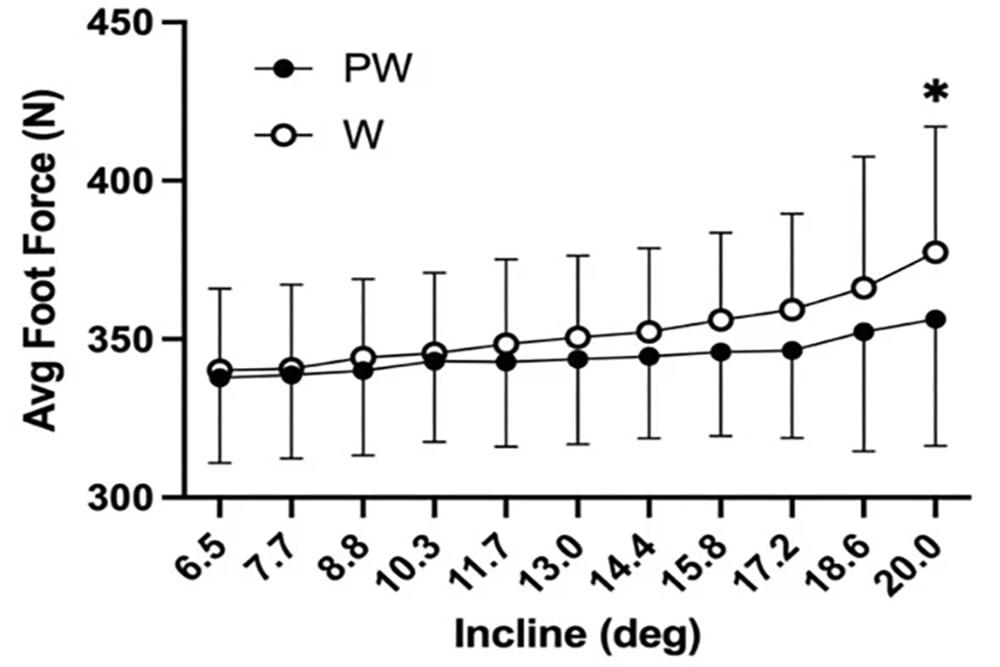

The graph below demonstrates the insole-measured foot forces as a function of incline, both with poles (black circles) and without (white circles). But the results also show that to get the most out of your trekking poles, you need to actively use them with some force and not just passively for balance.

The results shown in the graphs are from the treadmill tests but, outside, the trends were broadly replicated. Leg forces were around 5% lower during the outdoor hill climbs even though the subjects were 2.5% faster when using poles.

Conclusion: Do trekking poles really help?

Giovanelli’s tests found that using trekking poles reduces the foot force both on the treadmill and outdoors at varying degrees of intensity and concludes that the use of poles “saves the legs” during uphill climbs. However, he noted that the team found “no effects of poles on cardiorespiratory parameters across all tested conditions” meaning they don’t save or expend detectable amounts of energy.

Essentially, the prevailing picture is that using trekking poles helps you climb faster up steep slopes, not because they conserve energy but because they transfer load from your overworked legs to your underworked arms.

These latest results, combined with the 2020 review by Ashley Hawke and Randall Jensen, make for a compelling case for using trekking poles, particularly on steep uphill climbs or when carrying heavy loads. And, when you consider that trekking poles can also double as tent poles for lightweight shelters and, in the case of an emergency, as splints for damaged limbs, I wouldn’t hit the trail without them.

Editor’s pick

I’ve used a pair of Leki Lhasa collapsible trekking poles for years. The aluminium design makes them sturdy, durable and light, and I’ve always found the grip comfortable over long periods of use.

The REI spring sale includes up to 25% off trekking poles.

Enjoyed this post? pin it for later…