In her new book, Rachel Hewitt honours the women written out of outdoor history. Here, she explains why it was important to tell their stories

Rachel Hewitt is a critic, broadcaster and the bestselling author of several books including Map of a Nation: A Biography of the Ordnance Survey and A Revolution of Feeling: The Decade that Forged the Modern Mind. She has written for the Guardian, Telegraph, Financial Times, New Statesman and Times Literary Supplement and is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature. Beyond writing, she has appeared in the BBC’s Coast and Timeshift programmes and regularly participates in BBC Radio Three’s Free Thinking.

In 2019, Rachel lost five family members in five months. To cope with the grief, she turned to long-distance running across the wilds of North Yorkshire. In doing so, the inequities facing women in the outdoors and sports became all too apparent to her. She found that she couldn’t hit the trails without being cat-called or followed by men, or run or walk alone at night without fear.

As a result, she went in search of the foremothers who blazed a trail at the dawn of outdoor sports in the 19th century. During her research, she discovered that all too often women had been pushed to the periphery of outdoor sports and activities.

As a corrective, she wrote In Her Nature, a powerful blend of memoir and history that covers women’s struggles to access the outdoors and how running ultimately helped Rachel deal with her grief. We asked her to tell us more.

1. Your new book tackles women’s struggle to access the outdoors. What do you hope readers will take from it?

The book has two main messages. The first is that being active outdoors – running, walking, climbing or any number of activities that enable the body to move freely across the landscape – can be transformative for women, personally and politically. Sport helps us to know and care for our bodies.

The suffragist Mary Crawford wrote about how mountaineering grants women ‘confidence with every step’ and learning to move authoritatively in sport can have enormous knock-on effects in our everyday lives. I think running has made me much more aware of my own needs and more vocal in defending them.

This leads to the second message of the book: that because of the genuinely empowering nature of sport for women, misogynist men often direct their vitriol towards women being active outdoors. There’s a long history of men who are unhappy with the progress that feminism has made and target active women as a form of anti-feminist backlash.

Men drive women out of sporting clubs and competitions, leave us out of media coverage and intimidate us on the streets. Often, when men can’t reverse the progress of women’s rights in legislation, they turn to settings – like sports, streets or parks – where their behaviour is less regulated.

So a way of protecting women in these settings is to defend women’s access to sports and the outdoors through centralised mechanisms, like equalities legislation, robust prosecution of street harassment and transparency in the allocation of state funding to men’s and women’s sports.

2. How do you deal with harassment in the outdoors?

I hate it. It’s terrifying. You never know when a noise or comment from a male stranger might escalate into being chased or groped or assaulted. But I think there’s very little that women can do, as individuals, to make ourselves more safe.

I’ve looked at the circumstances in which men have murdered female runners in the last 30 years and many of those women were actively taking safety measures. Almost all of the women were running in daylight, most in busy areas (one woman was murdered while running in a park where families were playing) and many had set their phones or watches to act as trackers so their partners could follow their runs. And men still murdered them.

I think that, in public messaging around this area, there is a bit too much emphasis on keeping women ‘safe’ and not enough on the main goal which is protecting women’s freedom. The idea of keeping women safe can sometimes treat men’s violence as an inevitable fact of life and puts the onus on women to restrict their activity accordingly.

But women’s freedom – the freedom to be strong, active and comfortable in our own bodies and to move around the world with curiosity and joy – is incredibly important, and it’s so important to me these days that I try to prioritise it above niggling worries about whether it’s safe for me to go running on a deserted moor.

As a society, efforts to protect women from harassment need to concentrate on the men who perpetrate it, through a combination of legislation, policing, education and male allyship – male passers-by who challenge street harassers or who go into schools and talk to young men about why they feel that women have gained the upper hand, and why they target women outdoors in retaliation.

3. In researching the book, was there a woman you admired in PARTICULAR?

The central historical figure in In Her Nature is a remarkable woman called Lizzie Le Blond, who left her husband and baby son to live in the Swiss Alps for twenty years, where she accomplished climbs that made her one of the most famous mountaineers in the world.

I also write about ‘ordinary’ women who were active at the beginning of the outdoor leisure movement, who weren’t necessarily breaking records, but who found profound joys that were directly related to their experiences as women – and who also experienced many annoyances that resonate today, such as street harassment from men and a lack of outdoor clothing designed for female bodies.

I was particularly struck by a woman called Martha Patty Shaw, who showed extraordinary determination in her desire to explore and climb. She was widowed in the 1840s and had been left with severe disabilities after childbirth. When her mother died, Martha decided that a change was necessary in her life, so in 1845 she set off with her six children for travels around the continent.

In particular, she wanted to climb mountains, so she took her children to the Rigi massif in central Switzerland; the Brünig pass, between the Bernese Oberland and central Switzerland; the St Gotthard Pass; the Aare Valley; and Mount Vesuvius. She couldn’t walk, so she went up these mountains in a chaise-à-porteurs, a chair supported on long rods, which were carried by porters.

She wrote fascinating diaries about the experience of mountaineering from the perspective of a person with disabilities. She wrote about the geometry of movement in a chaise, the physical experience of being carried down extraordinarily steep slopes and the muscles she had to tense to prevent herself from slipping. It helped me see the landscape and outdoor sports in a completely different way from what I was used to.

4. What was the hardest thing about writing the book?

I suffered a number of bereavements while I was working on the book, including my father, my step-father and my husband. The book is partly about grief. It’s about how grief affects the body, and how I turned to running in the great outdoors to help me feel physically stronger and more comfortable again.

The book is also about a wider form of grief, which could perhaps be called ‘feminist grief’ – such as the sense of loss and dispossession that many women experience due to the inability to walk or run alone at night without fear.

I found it extremely hard to write about the people I’ve lost and my subsequent grief. I didn’t find it ‘cathartic’ at all. Instead, writing about traumatic events had the effect of returning me to them and emotionally and mentally having to reinhabit those periods in forensic details (not that I’ve ever left really them).

Also, the impact of bereavement is not just emotional – it’s also logistical. I’m now the sole parent to three children and that brings challenges such as finding the time and focus to ready the book for publication.

But I desperately wanted to have something to look forward to, so after my husband died in early 2022, I made myself get the book over the finish line and ready for publication in April 2023. I thought of it like planting bulbs in the dark, rainy days of autumn so that there’ll be something to look forward to in the spring.

Also, I think that there is a strange sort of consolation in the act of creating something new – like a book – out of loss. I found it helpful to be engaged in making something, generating something, at a time when it felt as if everything was being taken away from me.

5. Tell us about the travel that changed you. What region or trip impacted you most?

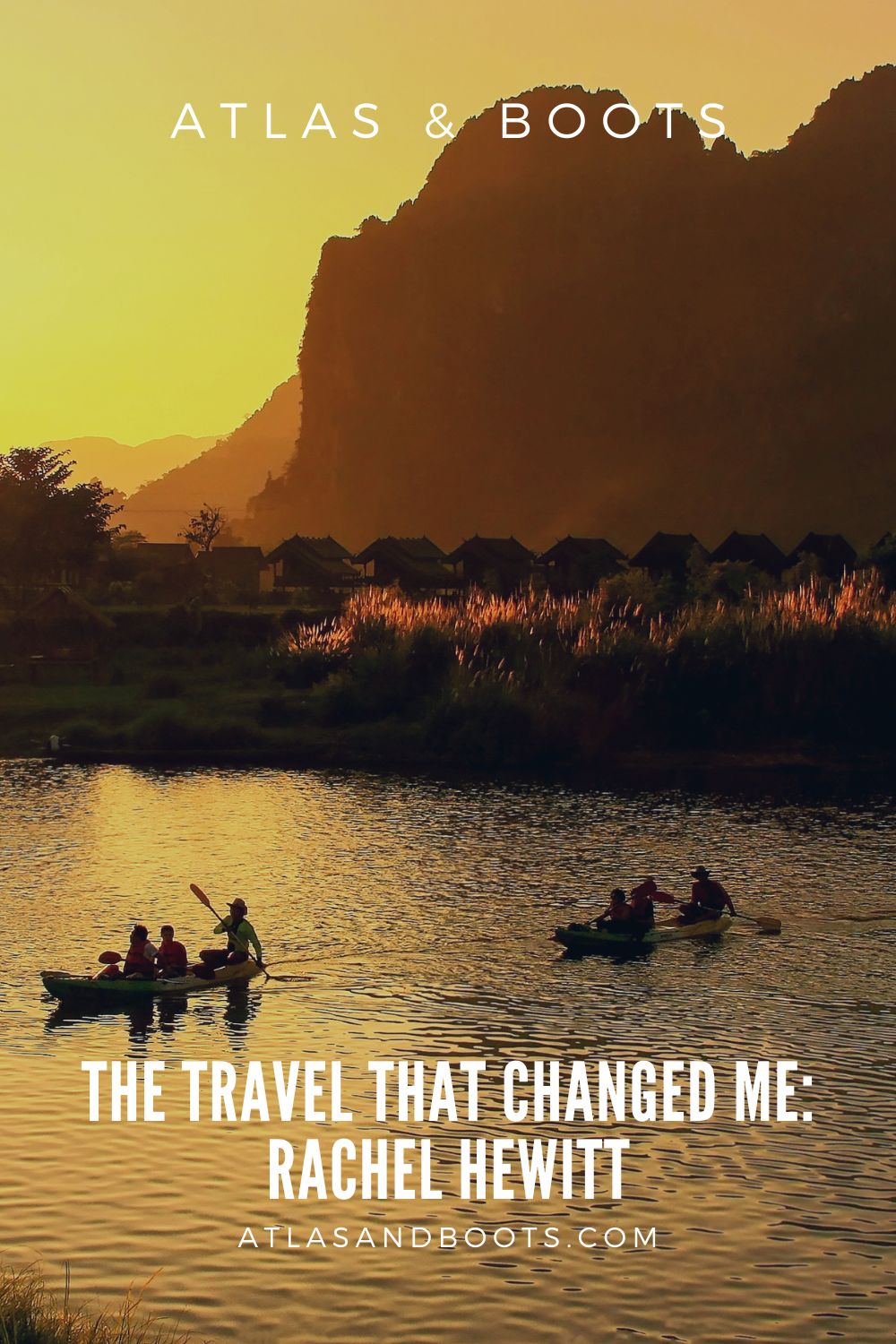

After my husband died, I took my children for an extended holiday to Australia, Vietnam and Laos. We went for about six weeks, with around a fortnight in each country (I’d have liked to have gone for longer, but I didn’t want to disrupt their schooling too much).

In particular, I loved visiting Laos. We stayed in Luang Prabang, and it’s perhaps the most beautiful place I’ve ever visited – the combination of stunning temples against the backdrop of densely forested hills and the winding Mekong River.

But it was the people who had the most profound impact on us. One of the effects of trauma has been that I’ve become immensely sensitive to noise and Lao culture places a high value on calm, quiet and politeness so in sensory terms, it was a very restful place to be.

I was also struck by the importance of women in Lao society. As Dervla Murphy found in her travelogue One Foot in Laos, often it’s the women who have practical responsibility for managing the family businesses while the men play an active part in childcare.

6. Do you still have a dream destination you haven’t yet seen?

The children and I are going back to Laos later this year – we can’t wait! And I’d really love to travel to Norway at some point, and to Switzerland in the summer. I’ve been to St Moritz in the winter but I’d love to see the mountains without snow.

7. Are you a planner or a see-how-we-goer?

Definitely a planner!

8. Hotel or hostel (or camping)?

Camping! I discovered the joys of camping very late: during the 2020 lockdown. And now I’m a total convert. I love being outside as much as possible, hearing the dawn chorus through the canvas and seeing the stars at night.

And it’s a brilliant holiday with children. Mine seem to find new friends within about 10 mins of arrival so I get to sit in a hammock with a beer and a book while they run around playing or splashing about in streams.

But in my experience, camping is either wonderful or rubbish, and it’s pretty dependent on the weather. Obviously, warm and dry is ideal but I can cope with warm and wet (or cold and sunny) too – but we’ve had one rainy, dark and cold camping trip and it was awful. We couldn’t get any clothes dry and were heartily sick of one another’s company by the end!

9. To guidebook or not to guidebook?

I like a guidebook, especially for maps. I don’t necessarily follow the suggested itineraries, but I find it useful – especially for short trips – to have a list of highlights and I do find the chapters on countries’ histories and political constitutions interesting.

10. Finally, what has been your number one travel experience?

I’m not sure if it’s my ‘number one’ travel experience, but I got a lot out of a trip in 2020 when I went ‘fast-packing’ along the Dales Way route in the Yorkshire Dales. It was the first time that I’d ever camped and I carried a lightweight tent, camping mat, sleeping bag etc all in a 25-litre running pack.

There was something incredible about being totally self-sufficient. I felt really free; not beholden to any bus or train times or check-in times at hotels. I could take the run at a very slow pace (which was lucky because it was hard work running with a laden pack!) and stop where I wanted for cups of tea or pints of beer. I felt quite invincible afterwards. I knew that I could look after myself.

Her Nature: How Women Break Boundaries in the Great Outdoors is a unique blend of memoir and history covering women’s struggles to access the outdoors and how running through the landscape helped the author deal with bereavement.

Enjoyed this post? pin it for later…